Since the turn of the year I’ve noticed the increasing presence of a company called Grammarly in my social media feeds, from friends thumbs-upping the service on FB to retweets of its stock language memes on Twitter.

For anyone unaware of it, Grammarly’s basically a grammar-checking app which, while appearing to be just a fancier version of Microsoft Word’s built-in document reviewer, actually bills itself “the world’s most accurate grammar checker”, helping “more than 3 million writers...perfect their written English” (monthly fee $29.95).

That’s an impressive claim. It may well be the world's best grammar checker, but that's not necessarily saying much because it turns out the platform isn't that accurate – reviews have shown that Grammarly regularly misses clear mistakes in checked documents, while flagging errors that don't exist.

That was never going to bother me as I'd never use it anyway, and wasn't going to pay to give it a go out of curiosity, so I was happy to see it recently publicise an infographic of its application of grammatical rules, entitled ‘Fifty Shades of Grammar’ to tie in with the release of the eponymous movie.

Let’s take a look at some of the gaffes they found.

The complex sentence? “I am a common man with common thoughts and I’ve led a common life.” Apparently Sparks needed to insert a comma after "thoughts" for it to make sense.

Hold on – isn’t this supposed to be an instance of a comma being used “when a semicolon would be more appropriate”? That’s a double-fail before we even get to the point that no, a comma is not required in such a basic sentence of two short clauses.

Neither is one required in the Hemingway example – and on top of that, if you are going to insert a comma where Grammarly has stuck one in, then you’d need another one too, ie. “have our books and, at night, be warm in bed together”.

Non-solutions for non-problems are what Grammarly are trying to sell here.

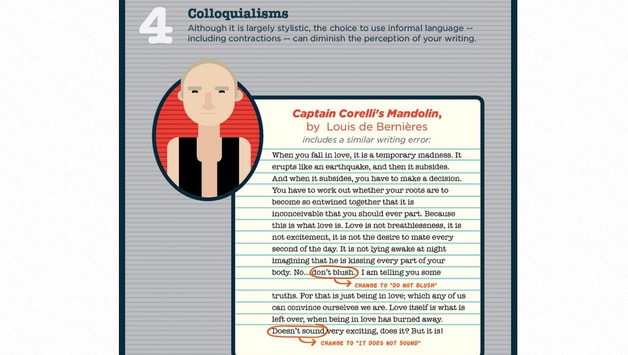

So no, you shouldn’t change “don’t” and “doesn’t” here to “do not” and “it does not” because in the real world that’s not how normal people speak to each other in conversation.

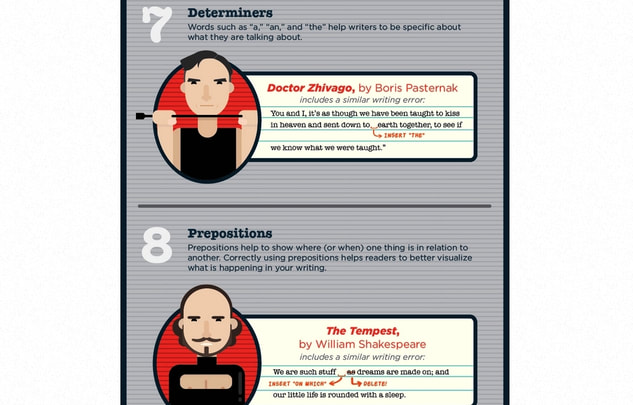

And what a surreal crock it turns out to be, with the infographic declaring that “down to earth” should be corrected to “down to the earth”, because, clearly, the original phrase just isn’t specific enough. So in Grammarly’s alien world someone might describe themself as a “down-to-the-earth guy”, whose favourite film might be 'The Man Who Fell to The Earth'?

And as for the following Tempest example, yeah fuck Shakespeare’s poetic verse and iambic pentameter, we need to help readers better visualise what he’s saying. And to do so, we’ll actually trash it by introducing an error where there wasn’t one before: “We are such stuff on which dreams are made on”. Two ons - sorted.

Which begs the question: on what planet is the original line unclear? Only in an alien world of demented anality so far away that no telescope could ever spot it. That’s where Grammarly lives.

Its infographic is the linguistic equivalent of scare tactics used by certain political parties or tabloids to frighten the public with illusory problems. And less confident people will unfortunately swallow it and hand over their $30 a month and actually become poorer writers because of it.

At best, Grammarly's service is better than nothing, for those who don’t have access to Microsoft Word or an equivalent, or for those who might want a second opinion, maybe for students double-checking an important essay. But as for claims of being the world's leading grammar authority helping people “perfect their written English”, on this evidence it’s a sham and a scam that should be given as wide a berth as possible.

If I ran this blog post through its programme it would probably flag that last line as the passive voice and not clear enough in meaning or something. I just wish its creators would come down to the earth!

Liked this? Read this: A Week in Israel with Britain's Biggest Bullshitter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed